"You are to be holy to me because I,

the LORD, am holy." (Lev. 20:26)

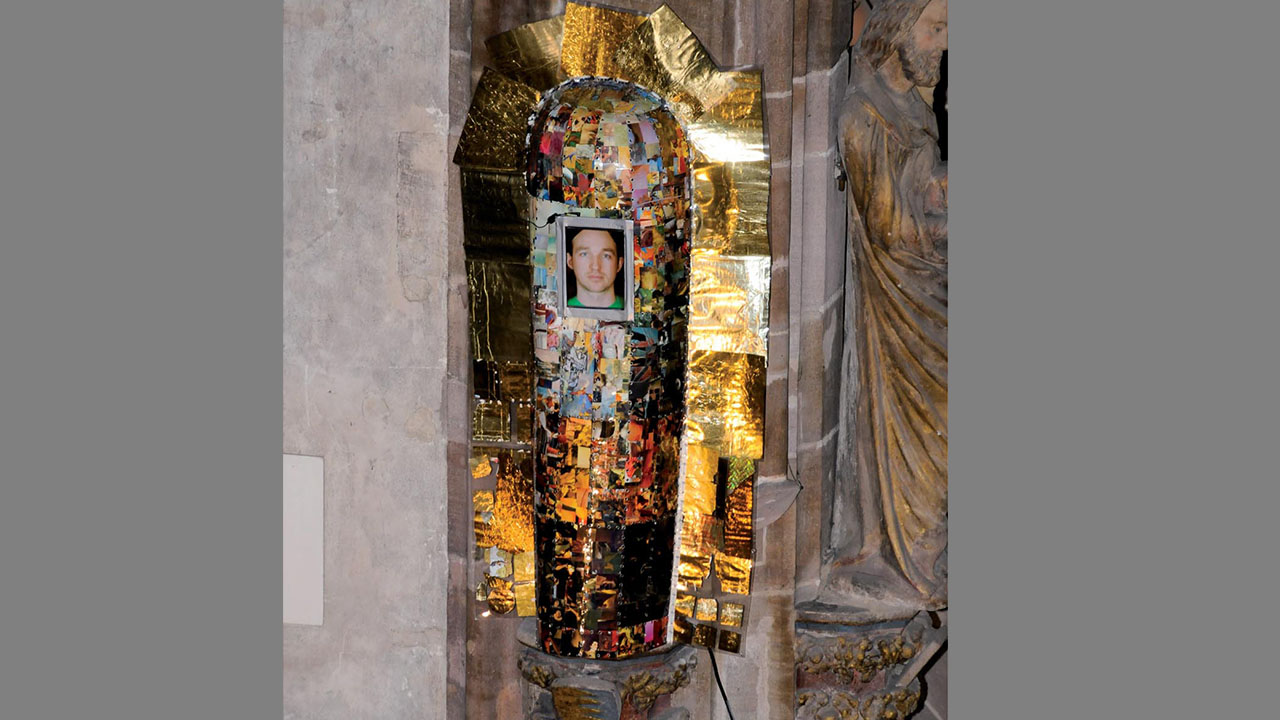

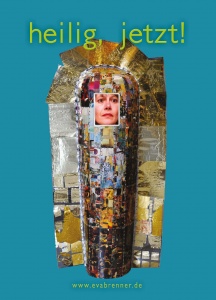

work in progress,

laminated figure, life-size

+ digital picture frame (100 portraits)

No.1 Frauenkirche, Nürnberg, März 2010

No.2 Herz-Jesu-Kirche, Erlangen, Allerheiligen 2011

No.3 Bamberger Dom, April 2014, anlässlich der Heiligsprechung der Päbste Johannes XXIII und Johannes Paul II

No.4 St. Hedwigs-Kathedrale, Berlin, Dezember 2017

Please also note the current website heilig, jetzt! about this project. Holy, now!

Portrait photography for the holy figure by Uwe Niklas. Uwe Niklas,Photography by Uwe Niklas,, Michael Zirn and Chandra Moennsad..

A figure of a saint made entirely of scrap -

with a digital screen as a field of vision, on which 100 portraits appear every 30 seconds.

Holy?

What is that? And who is that?

All of us who follow Christ are holy, are saints.

And why are there saints then? Are they even holier? And why?

Eva Brenner's work is abouttranslating the iconography of the past, which has become strange and incomprehensible to us, into the present.

Ikonografie der Vergangenheit in die Gegenwart zu übersetzen.

Eva Brenner, born in 1963, studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Nuremberg under Prof. Hanns

Herpich and Prof. Ottmar Hörl.

The corpus of the saint's figure consists of the art history of the Occident

("Art"-booklets, year 1982-1992, chronologically sorted, extracted, laminated and rearranged

and riveted according to the criteria light/dark and cold/warm).

The gloriole/ halo shines out of laminated civilisation waste,

coffee vacuum packs, chocolate and

candy wrappers.

The figure's field of vision contains a digital screen.On this screen,

100 portraits appear, which

follow each other in an endless loop at 30-second intervals.

The portraits will be taken in a

photoshoot on location,

the invitation is open to everyone.

work in progress

laminated figure, life-size

+ digital picture frame (100 portraits)

No.1 FrauenkircheNuremberg, March 2010

No.2 Herz-Jesu-KircheErlangen, All Saints 2011

No.3 Bamberger DomApril 2014,

on the occasion of the canonisation of Popes John XXIII and John Paul II

No.4 St. Hedwigs-KathedraleBerlin, December 2017

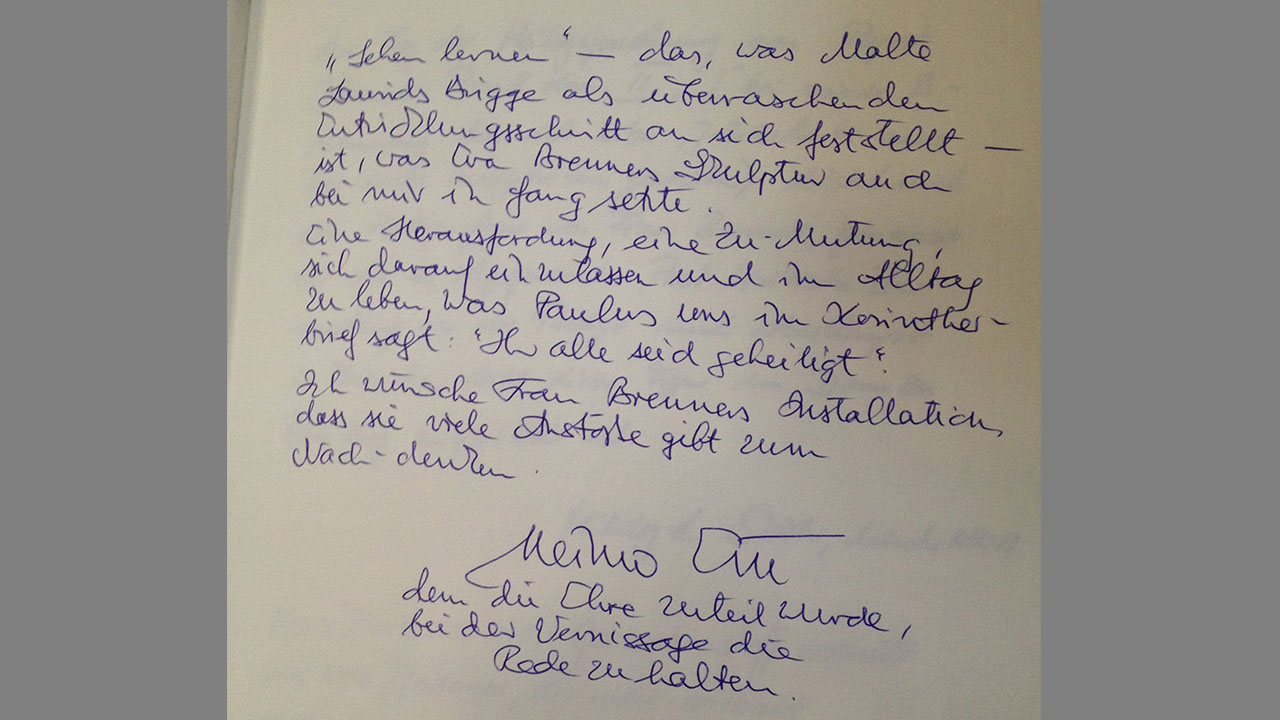

Introductory speech by Prof. Dr. Heimo Ertl

Eva Brenners Skulptur „Moderne Heilige“

im Bamberger Dom, am 27.4.2014

Ladies and gentlemen, in the "Notes of Malte Laurids Brigge", Rainer Maria Rilke has Malte say: "I am learning to see. I don't know what it is, everything enters deeper into me and doesn't remain standing where it used to stop. I have an inside that I didn't know about. Everything is going there now. I don't know what is happening there." And one paragraph later, Malte picks up on this thought again by asking, "Have I said it already? I am learning to see. Yes, I'm beginning. It's still working poorly. But I want to make the most of my time. That, for example, it never occurred to me how many faces there are. There are a lot of people, but many more faces, because everyone has several. There are people who wear a face for years, of course it wears out, it gets dirty, it breaks in the creases, expands like gloves you've worn on the journey. These are thrifty, simple people. They don't change it, they don't even have it cleaned. (...) Other people put their faces on incredibly quickly, one after the other, and wear them out. (...) They are not used to treating their faces with care, their latest one is through in eight days, has holes, is paper thin in many places, and then little by little the base comes out, the non-face, and they walk around with it."

This passage came to mind, ladies and gentlemen, when I first saw Ms Brenner's sculpture "Modern Saints" with the 100 faces, exhibited here in Herz Jesu . And I felt like Malte, I "learned to see". Your work of art set in motion a new "way of seeing", thoughts about art and saints, which I, as a Catholic, would like to talk about with you today in a self-critical way, linking all denominations - not a bad topic on Reformation Day and the day before All Saints' Day - the saints and art. Art today is no longer, as Marc Chagall put it, "the incessant attempt to compete with the beauty of flowers". The art of our time does not strive for the title "beautiful", however one would define it today. Rather, it wants to be exciting, thrilling, intelligent, disturbing, shocking, yes, provocative, but not "beautiful as a flower".

This passage came to mind, ladies and gentlemen, when I first saw Ms Brenner's sculpture "Modern Saints" with the 100 faces, exhibited here in Herz Jesu . And I felt like Malte, I "learned to see". Your work of art set in motion a new "way of seeing", thoughts about art and saints, which I, as a Catholic, would like to talk about with you today in a self-critical way, linking all denominations - not a bad topic on Reformation Day and the day before All Saints' Day - the saints and art. Art today is no longer, as Marc Chagall put it, "the incessant attempt to compete with the beauty of flowers". The art of our time does not strive for the title "beautiful", however one would define it today. Rather, it wants to be exciting, thrilling, intelligent, disturbing, shocking, yes, provocative, but not "beautiful as a flower".

"Pro-voke" means as much as "evoke", "challenge". A work of art that provokes challenges us to come out of our accustomed thought structures, "points of view" and positions, demands a statement instead of pleasurable enjoyment, perhaps unsettles by the insecurity linked with it. What Ms Brenner's installation provokes in us depends largely on us. For "art is nothing (at all)," says Ben Willikens, "as long as it is not redeemed through dialogue, communication with the viewer. And it keeps slumbering in this nothingness for a long time as long as the viewer is not finished with his work, with looking."

What is there to look at? At first, I think, our gaze is caught by the mosaic of particles of colour that shining like a precious cloth clothe a domed body reminiscent of a mummy's sarcophagus. A closer look reveals that countless small excerpts from paintings of different epochs, joined together, create this effect, which emanate the impression of something precious, venerable and mysterious. The Pedestal at the level of the statue of the Sacred Heart opposite underlines its significance.

Near the place where the portrait of Pharaoh is on the mummy, mummy, faces of members of this parish light up incessantly on a screen at regular intervals. One after the other, men, women, children, old, young, happy, pensive, curious and detached. One hundred faces, one hundred people. Each of these pictures says more than a thousand words about the experiences of hopes and disappointments, about longings and fulfilments, about strains and rewards, in short, about "the unique, one-of-a-kind, inexhaustible, bottomless, the enigma that has a name", as the Karlsruhe artist Emil Wachter once described the mysteriousness of the human countenance.

The combination of an archaic-looking corpus and a flat screen with electronic image sequences is confusing. It provokes formal-aesthetic questions and the question of what this kind of representation does in relation to the images of saints we have in our heads, or should I say used to have? In the Middle Ages, saints were painted on a gold background, a symbol of eternity, or they were placed on pedestals in their golden robes. In this way, their otherness was expressed artistically. (This is still echoed in Ms Brenner's design, but is "broken" by the picture show). Not much left of people. The axe was most clearly laid on the veneration of saints during the Reformation. For Luther not only eliminated the abusive excesses of the contemporary cult of the saints. What bothered him was that, as he said, "the people put more trust in the saints than in Christ himself". So he abolished the veneration of saints altogether on the grounds that "there is only one reconciler and mediator between God and man, Jesus Christ". From 1530 onwards, the "Augsburg Confession" only provided for the saints to be "commemorated for the strengthening of faith" and to "take their good works as an example".

The combination of an archaic-looking corpus and a flat screen with electronic image sequences is confusing. It provokes formal-aesthetic questions and the question of what this kind of representation does in relation to the images of saints we have in our heads, or should I say used to have? In the Middle Ages, saints were painted on a gold background, a symbol of eternity, or they were placed on pedestals in their golden robes. In this way, their otherness was expressed artistically. (This is still echoed in Ms Brenner's design, but is "broken" by the picture show). Not much left of people. The axe was most clearly laid on the veneration of saints during the Reformation. For Luther not only eliminated the abusive excesses of the contemporary cult of the saints. What bothered him was that, as he said, "the people put more trust in the saints than in Christ himself". So he abolished the veneration of saints altogether on the grounds that "there is only one reconciler and mediator between God and man, Jesus Christ". From 1530 onwards, the "Augsburg Confession" only provided for the saints to be "commemorated for the strengthening of faith" and to "take their good works as an example".

Today, however, let's admit it, the saints no longer seem to be quite in demand in our church either, or, as Walter Nigg puts it more amiably: "It has become strangely quiet about them." They have largely vanished from the religious practice of Catholic Christians and, where cultural heritage management did not prevent it, also from many church buildings themselves. Out of sight, out of mind? In some places, they have been given a place in the parish hall as a kind of "Granny flat", but this is more likely to have been done for reasons of interior design or interior architecture than because one would expect this change of location to revive the veneration of the saints. This treatment of the saints - an image of the dimming of these figures in the consciousness of the church?

"Intercession, miraculous power and relics of the once so venerated"Holy Helpers",the patrons of a church, titular saints and patron saints of a guild", play "an everdiminishing role in the life of faith of modern Christians", laments Peter Manns in his book "Die Heiligen in ihrer Zeit" (The Saints in Their Time). Saint Mary is not quite so drastically affected by this development, especially in southern Germany, but when you see the statuette of Mary, if you notice it at all in the large Herz-Jesu-Kirche (“Sacred Heart Church”), you might get the impression that she too is hurrying after the other saints who have already disappeared from view.

Of course, neither the Reformation nor rationalism is to blame for the factthat the saints are no longer popular with us today. It sems to me that also their false stylization in the fields of theology an art have played a part here. The well-intentioned, but inadequate and untrue whitewashing of their vitae through hagiographies has often turned the saints into one-dimensional, bloodless, lifeless figures that no longer appeal to modern Christians. And the visual arts - especially through their epigones - have created stereotypes as images of saints, in which a blue or red coat on a figure is enough to make the viewer think of Mary or Jesus. Rilke's Malte Laurids Brigge would place these representations of saints in the group of those who have only ONE face, worn for years, centuries, broken in the creases, worn out.

Yet historical-critical testimonies of some saints showthat they very well had "many faces", that they were, in part over long periods of their lives, by no means an "ideal human being" or "paragon of virtue". On the contrary, many "full-blooded saints" were anything but convenient Christians, and the Church, for many of them, impeded the "ascent to the honour of the altars considerably" (Peter Manns).

The diversity of the individuals of the saints is expressed by Ms Brenner's random and seemingly arbitrary juxtaposition of individual images on the corpus and their interconnectedness. On the one hand, the pictorial scenes with people from different epochs symbolise the great community of saints that has grown in the course of history and to which we commit ourselves in the Creed. Each of these small pictures represents for me, so to speak, a facet of how a very concrete person lived their becoming holy and being holy - in their unmistakable, unique and singular way. There is no such thing as a saint as such, as a type, but only very concrete people who, in their time, responding to the respective challenges, put their lives so radically into God’s and the world’s service that, in a manner of speaking, we can call them the gospel in practice. The synopsis of these facets opens up a whole new perspective on the saints' lives and their lives. The synopsis of these facets opens the view for the richness of the canonised saints and is to be constantly and differentiatedly adjusted. It is an effective paradox that precisely the multitude of portraits, the changing faces, the hundred pictures that have been taken, warn against "forming a picture" of just one picture.

But the portraits of the parishioners have another message for me. All of us who are baptised share in the kingship, priesthood and prophethood through the anointing with charism. It applies to all of us, what is written in 1 Corinthians and what unites us with the protestant Christians, namely that we are already "sanctified" in baptism by Christ and the Spirit of God: "You were sanctified", it says. (1 Cor. 6: 11). This word reminds us that the "communion of saints" of the Creed has never been meant as just a kind of closed society, an exclusive club, “up there” in heaven, but includes all of us who are alive. In this respect, the faces of the parishioners direct our gaze downwards, towards us and our journey through life.

The screen, noticeablly, is not placedwhere the head of a mummy would be, but is offset to the left, downwards, exactly where the human heart beats. From there the faces look at us - a call to be "alive" and invigorating in our communities, in the world, to put into practice the promise "You are sanctified"?

Ladies and gentlemen, the sculpture exhibited here, like every work of art, is by its very nature dialogical, designed for a counterpart, a viewer, as I said in my introduction. The aesthetic concentration of this installation, its unusual formal language and its degree of abstraction are not an invitation to "small talk". Rather, they demand our attention, they are literally "demanding", like a good dialogue in which, if you are lucky, you come closer bit by bit and understanding grows, where you cannot simply seize the position of the other person with a wave of your hand. The installation with its mix of materials, the reduced rigid body form in conjunction with the rhythmically changing faces on the screen challenge us to perceive them and to reflect on our own perception, to engage in what Marcel Proust calls a person's "actual voyage of discovery". This, he states, does not consist in getting to know new regions, but in seeing the seemingly familiar with different eyes, in "discovering", perhaps rediscovering. Here, too, the "meaning" of a work of art depends essentially on whether and how the viewer engages with it with open eyes and senses. A quick judgement - as so often - only judges us.

Ladies and gentlemen, the sculpture exhibited here, like every work of art, is by its very nature dialogical, designed for a counterpart, a viewer, as I said in my introduction. The aesthetic concentration of this installation, its unusual formal language and its degree of abstraction are not an invitation to "small talk". Rather, they demand our attention, they are literally "demanding", like a good dialogue in which, if you are lucky, you come closer bit by bit and understanding grows, where you cannot simply seize the position of the other person with a wave of your hand. The installation with its mix of materials, the reduced rigid body form in conjunction with the rhythmically changing faces on the screen challenge us to perceive them and to reflect on our own perception, to engage in what Marcel Proust calls a person's "actual voyage of discovery". This, he states, does not consist in getting to know new regions, but in seeing the seemingly familiar with different eyes, in "discovering", perhaps rediscovering. Here, too, the "meaning" of a work of art depends essentially on whether and how the viewer engages with it with open eyes and senses. A quick judgement - as so often - only judges us.

Let me quote Rainer Maria Rilke once again.He writes in his famous poem "Archaic Torso of Apollo" what can happen to those who engage in an encounter with a work of art with all their senses and eyes open, in his case the contemplation of the ravishingly beautiful marble torso of an ancient statue of Apollo. The fascinated admiration of this work of art causes the roles of viewer and viewed to suddenly reverse. It is now the stone in which "his looking, only trimmed back, holds and shines". It flickers "like predator skins" and "bursts out of all its edges like a star".

Das Gewand der Heiligkeit von Thilo Westermann zu

Eva Brenners Kunstprojekt "holy, now!"

As an originary Western project, philosophy has over the centuries outstripped mystical-religious tendencies and continues to dominate contemporary society. Philosophy cannot recognise the foundations of theology as rational and thus capable of argumentation, because by incessantly struggling for knowledge under the maxim of rationality, it lacks the necessary instruments to allow what is only believed, felt or empirically hardly verifiable to be considered true. Thus, it does not continue the traditional doctrine of the glory of God without reflection, but critically questions its foundations in order to expose them as shaky, unacceptable foundations of any construct of faith. According to the rules of logic, the one God can no more be verified than various deities. Thus, the choice of whether and in what to believe remains a personal dilemma for each person to decide.

The replacement of the dark age of mercilessly imposed religious doctrines by enlightened religious freedom necessitated a new canon of rules for successful coexistence, which no longer legitimised itself by the grace of God, but as an ethical-philosophical work of thought. Today, the equality of all people as the basis of democratic forms of society is defined independently of descent, gender or sexual orientation. Church and faith take a subordinate position in this context, which should make merit for the salvation of people, and whose mission, in contrast to extra-ecclesiastical, charitable institutions, is directed towards a life under God’s sign.

The idea of caritas remains closely tied to ideas of wholeness, which can be found in the cult of saints and the effort to live as holy a life as possible. What is generally considered holy is that which is characterised by a special closeness to God. Accordingly, the German word for "holy"- “heilig” - is etymologically derived from "heil" ("whole"), which is thought of as a holistic merging with God. Here, aspects oriented towards the next world can be distinguished from those oriented more towards this world: For the needy human being, becoming one with God is not only conceivable after death, but already during life. Because of man's likeness to God, holiness is already inherent inevery individual from the very beginning. A yardstick for the holiness of one's own life can be the orientation towards Jesus, who as God in human form embodies an ideal life in an exemplary way.

His selfless thinking and acting is revered as an ideal, which is celebrated as the greatest possible closeness to God (namely identification with him) and thus as perfect wholeness. Accordingly, every human being is more or less holy, depending on how strongly he or she adheres to the canon of rules exemplified. The long-stirred up fear of having to atone for one's sins posthumously in the torments of hell in order to get close to God again was rationalised by the reassuring feeling of omnipresent holiness and closeness to God.

Eva Brenner's art project "holy, now! No. 1 " in Nuremberg's Frauenkirche ("Church of Our Lady") celebrates the holiness of each individual instead of painting a medieval pessimistic picture of the sinfulness of the world. Like a colourful cocoon, her figure hovers above a vacant console north of the choir and thus joins the older representations of saints in the choir room. In contrast to these representations of Mary, John the Baptist, the Three Kings and St. Wenceslas and St. Ludmilla, which were donated by patricians in the 1360s, Brenner's figure cannot be identified as a specific saintly personality. Attributes were deliberately omitted and the figure was reduced to a geometric-abstract cylindrical form, so the unusual way in which it was made is initially confusing. Instead of chiseling it out of a block of stone, Eva Brenner assembled her figure of a saint from the stock of images in the monthly art magazine “art”: The representations of saints depicted during a decade (1982-1992) were neatly excerpted with a scalpel and sorted according to the date of origin of the artwork depicted in each case in order to be assembled according to the compositional criteria of warm to cold and dark to light. The subsequent shrink-wrapping not only stabilised the paper cut-outs, but was also reminiscent of a sealing of the "picture treasure" similar to a museum archive for preservation for posterity. Finally, the foils were riveted together at the corners to form the cylindrical shape, which is ennobled by a shiny aureole to become an icon. On closer inspection, however, the halo turns out not to be a mystically shimmering precious material, but laminated civilisation waste. Its construction from everyday image and waste material demystifies Brenner's figureof a saint and thus turns it into a profaned version of the neighbouring sculpturesof saints in the choir.

The non-fixability to a specific personality and the emptiness inside also lend the figure something transitory and make it appear as a placeholder. Accordingly, a small monitor shows its changing "face". In an endless loop, portraits of people who had themselves photographed for Eva Brenner's project are faded in. By "lending" their face to the anonymous figureof a saint and having it appear on the screen, the portrayed person figuratively slips into Brenner's cocoon form. In this way, the shell of the saint is symbolically slipped over them and the previously empty shell is simultaneously transformed into an individual image, which now allows the portrayed person to appear as a saint themselves. Their personal strokes of fate and coping strategies are juxtaposed with the martyrdom and willpower of the canonically venerated saints. In the church room, the portrayed person does not achieve the five seconds of fame predicted by Andy Warhol, but appears for a brief moment in all the holiness of their own life. The question of legitimacy (Can anyone be a saint?) thus ends in the statement of the wholeness of individual life (Every individual is already holy!).

Eva Brenner plays here with the idea of the multiple. Although she had only one object installed in the Frauenkirche ("Church of Our Lady”), she brings a multiplicity of figures of saints into the sacred space with the same form. This is achieved by combining individual portraits with a general corpus; the different life stories of those depicted on the monitor correspond in each case with corresponding fragments of the image-rich cylindrical form. The shell of laminated images thus becomes a couture that clings to the individual body and life of its wearer (or the portrayed). The "dress" of the trained tailor Eva Brenner fits everyone in principle, because the body of her figure is woven from the abstract fabric of (art) history, with which everyone who believes in it can identify.